Mati Granica Takes Home Student Oscar For AI Art ‘flower_gan’

Innovative fusion of technology and creativity.

In an age increasingly shaped by algorithmic aesthetics and technological acceleration, the boundaries of art and artificial intelligence continue to blur. One striking voice in this evolving dialogue is Mati Granica, a London-based visual artist whose work interrogates the systems driving our digital futures. Granica’s latest project, flower_gan, has garnered international acclaim as a winner of the 2025 Student Academy Awards (Oscars) in the Alternative/Experimental category.

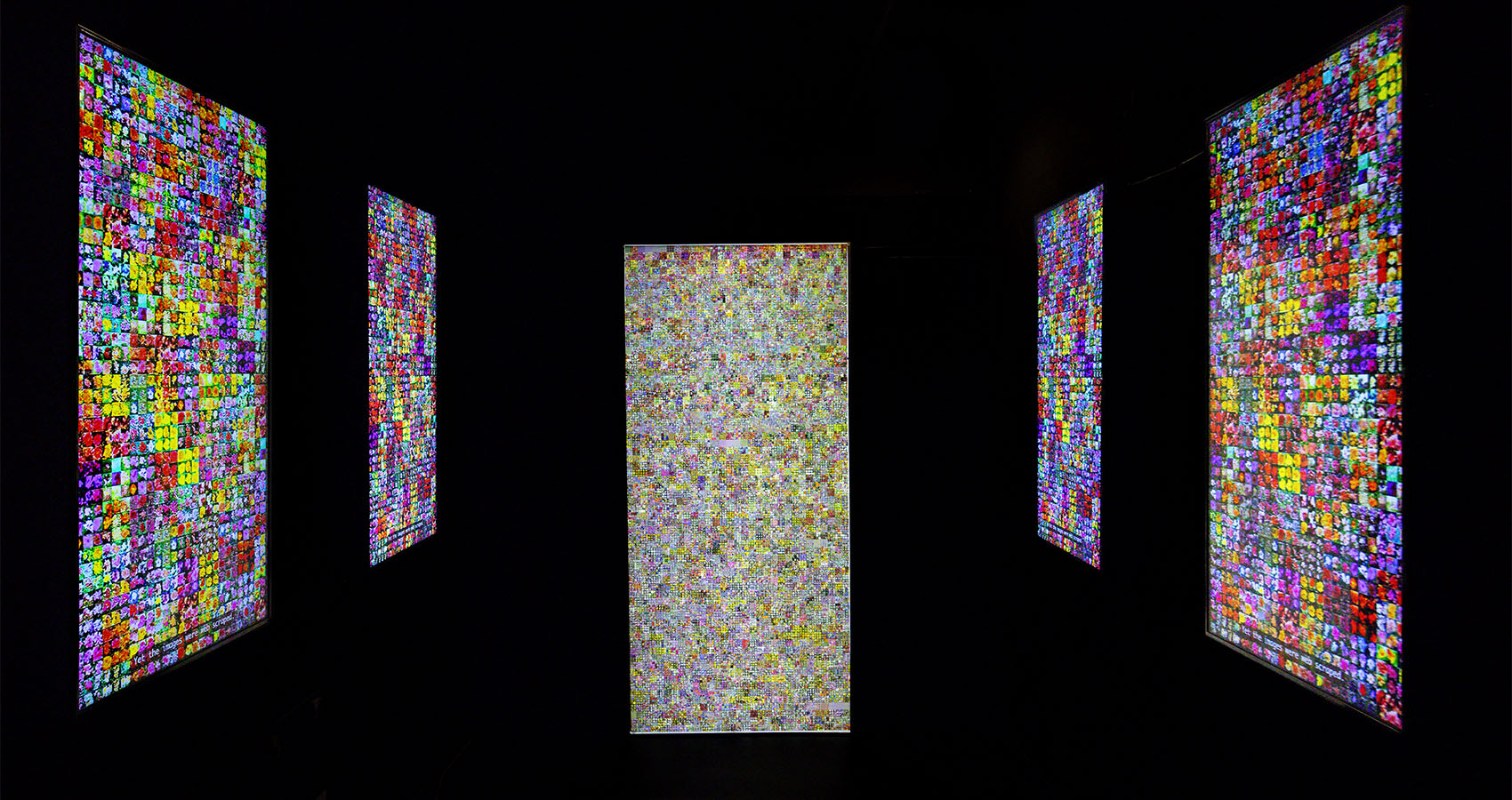

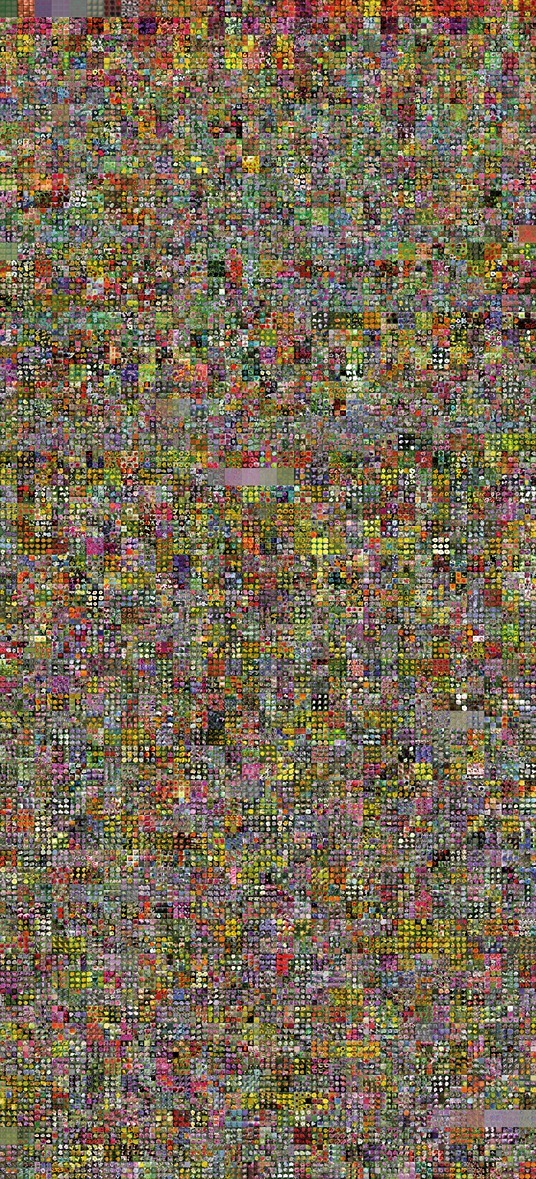

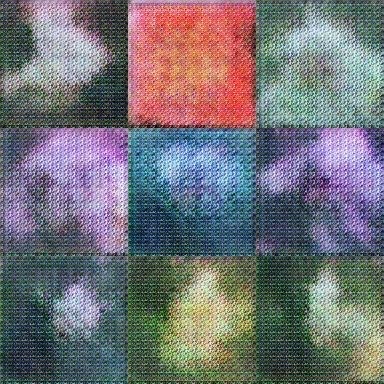

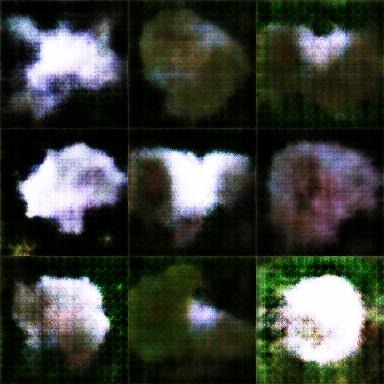

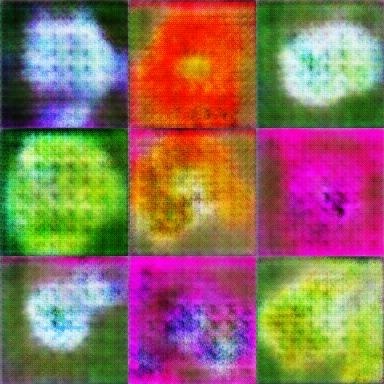

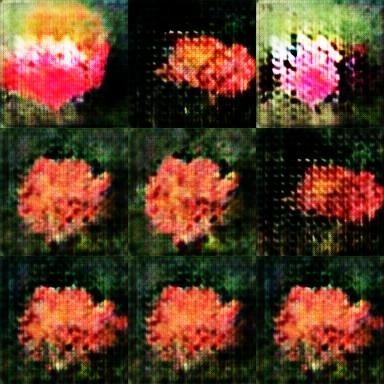

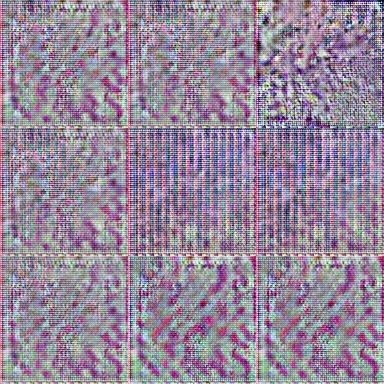

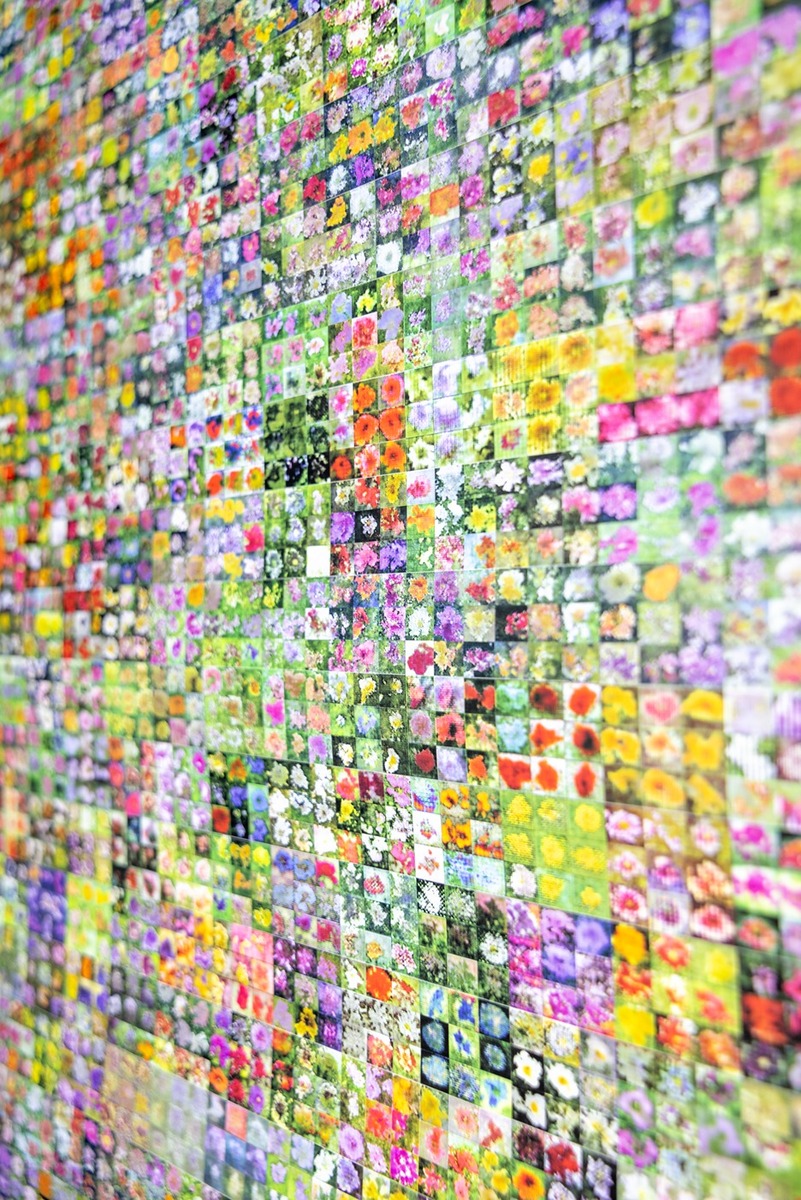

Built on a custom generative adversarial network (GAN), flower_gan attempts and repeatedly morphs to create images of flowers, offering a poetic yet unsettling meditation on the environmental contradictions of AI development. The project’s 27,616 machine-generated images, distorted and abstracted beyond recognition, reflect both the ambition and excess of techno-capitalist systems.

In this interview, Granica discusses the conceptual foundations of flower_gan, the paradoxes of using AI to critique AI, and what it means to make art in an era defined by ecological and technological crisis.

Granica, what was it about flowers, a centuries-old artistic motif that felt like the right vessel for exploring AI’s distortions?

Flowers are a subject I’ve explored before, particularly in my film Synthetic Organics. For flower_gan, I wanted to take something iconic that had been translated through various mediums across history, and run it through modern technology. Through the AI, the flowers are no longer something recognisable.

I was drawn to flowers because they are inherently contradictory: often symbols of beauty and ecology, yet in reality are produced as industrial goods; mass produced, genetically engineered, and farmed in ways that are far removed from anything ‘natural’. A store-bought flower is already a distorted version of our perception of a flower; the project simply takes that distortion further through machine learning.

Artificial intelligence and flowers also share historical and economic parallels. In colonial times, flowers were extracted from native lands and transported to Europe without consent; AI today depends on the extraction of data from unconsenting individuals, as well as minerals from the Global South, to fuel growth in the Global North. Their financial trajectories potentially align: the arguably speculative financial boom echoes the Dutch tulip mania in the 17th century. And just as the global flower trade relied on large shipping networks, AI depends on the hidden infrastructure of data centres and energy; systems of extraction hidden away from consumers.

Watching flower_gan spit out thousands of images, when did it shift for you from a technical experiment to something that carried real emotional weight?

I first really felt it when I left the system running for a few days and came back to tens of thousands of images. The volume was overwhelming. I put them into a contact sheet, and I really felt the scale of what I’d created. It stopped feeling like a technical experiment and felt almost intimidating. I also felt a real sense of responsibility, which was when I realised what the project should truly be about. That moment shifted the project conceptually for me. The excess of images reflected broader questions about overproduction, in AI and in capitalism, where the output became detached from intention or need.

You’ve described the project as hypocritical, using AI to critique AI. How do you personally sit with that contradiction? Does it gnaw at you, or energize you?

The contradiction initially frustrated me, but grew into a key tension that I was really interested in pursuing.

The idea of hypocritical art first came to me through my engagement with climate-focused projects, where I noticed many works directly contributed to environmental degradation through their production. I accept that when creating art around enormous subjects like climate or technology, complicity is almost unavoidable. My personal view is that, more often than not, the material costs to create art are outweighed by the impact it can have on people and the conversations it can encourage. There’s a net positive.

What frustrated me was not the complexity of artworks, but the lack of acknowledgement. That’s why I wanted to make work that creates space to reflect on the artist’s role and impact. I wanted to encourage nuance and for audiences to sit within the tension that arises from hypocrisy. I want to facilitate conversations about how we can exist in a world where we’re so surrounded by these systems that we can’t escape them, and wonder how we can critique a system we’re stuck in. These conversations energise me.

Building a live carbon tracker into an artwork is a bold move. What surprised you most when you saw the real-time costs of your creation?

What really surprised me was how it held my attention. It was really unsettling. I spent far too long fixated on the tiny set of numbers rising on my computer. In the grand scheme of things, the numbers weren’t shocking; the project is tiny compared to a commercial LLM or diffusion model. Yet the simple act of watching a number slowly tick up every second immediately gave me a sense of accountability. I could physically decide whether energy was used or not. It visualised the usually invisible act of energy use, and it was genuinely horrifying when I imagined scaling the project up to the size of the AI systems we see today.

Some of your dataset images still bore watermarks. Did encountering those artifacts change how you think about authorship, ownership, and consent in AI art?

I genuinely laughed in disbelief when I first saw a watermarked image in the dataset. Up until then, I had (naively) assumed it was built from original material. Clearly, I was wrong. Beyond the ethical issue of images being scraped without consent, it also felt strangely amateur that such obvious artifacts slipped through.

What stuck with me was how automated and unconscious the process is. No human is manually collecting thousands of images; a system is activated, and the machine does the rest with little intervention. That absence of human oversight was disconcerting and made the whole process feel detached from responsibility. It almost gives a sense of plausible deniability, which it shouldn’t.

These discoveries reinforced my frustrations around ownership in AI. There is no ownership. Everything on the internet seems to be fair game, which we didn’t sign up for. The fact that intellectual property can be used to train systems that will essentially regurgitate a manipulated version of that input is terrifying.

How did your time at London College of Communication shape your willingness to push into experimental, critical, even uncomfortable territory?

My time at LCC really encouraged me to take risks and to push my work into new directions. I arrived in London as a fairly traditional landscape photographer, and while I still love that craft, my strongest work has since drifted far from it. I vividly remember that right from the start, we were pushed to create something that had never been seen before, which was a bit of a shock for me. I expected to focus on making beautiful images, but creating something new quickly became the priority. That shift in mindset was formative, and I can see a clear point where I fully embraced it.

The teaching also placed a huge emphasis on criticality of ourselves, our practice, and the world around us. To ignore the problems we face is a political choice, and my education at LCC made me more conscious of that reality. It gave me the tools and the confidence to engage with the issues that were subconsciously occupying my mind.

This is thanks to the environment, which was always safe and uplifting. It was a place to try, to experiment, and often to fail. But crucially, it was a place to get back up and keep trying. The support from my peers and tutors cannot be understated, and flower_gan would not exist without their help.

Now that you’ve won at the Student Academy Awards, do you feel the recognition affirms your critique or risks pulling your work into the same systems it resists?

Winning a Student Academy Award is an enormous honour. It’s heartwarming that an organisation as prestigious as The Academy embraces work that deviates from traditional filmmaking and encourages innovation. It’s also brilliant that The Academy elevates films that discuss and challenge the systems that surround us in the present day, and I’m incredibly grateful that my work can contribute to that conversation.

At the same time, I am aware of the contradiction the question points to. By receiving recognition from such an established institution, there’s always a risk that the work gets absorbed into the very structures it critiques, becoming a kind of commodity itself. That tension is unavoidable, but I also think it proves the point: flower_gan is about hypocrisy and complicity, and its trajectory reflects that. For me, what matters most is the conversations that are encouraged. If an award provides a platform for more people to engage with these questions, then I see that as a productive use of the system, even if it comes with its own contradictions.

Coming from Poland and now working in London, how have those two cultural environments shaped your view of technology, ecology, and art’s role in that dialogue?

I was born in a city in Poland shaped by coal mining and heavy industry, and spent most of my childhood in an industrial town in England. In both places, I was surrounded by systems of production and consumption, and art wasn’t a big part of daily life. Early on, that gave me a very tangible sense of how technology and industry shape the environment, but I didn’t have the tools to reflect critically on it.

Moving to London changed that. Being immersed in a creative environment and receiving an education that encouraged experimentation made me more aware of how technology, ecology, and culture intersect. I started to see art as a way to question and engage with these systems. It also allowed me to revisit my experiences in Poland and England in a more critical way, understanding the environmental and social impacts of industrial life. I learned the potential for art to open dialogue around these issues, and I’d love to engage more with the Polish art scene.

When people encounter flower_gan, do you want them to feel seduced first and then unsettled or the other way around?

The intention is definitely to seduce first. I want the work to pull people in through curiosity; through the beauty, the scale, and the strangeness of the imagery. At first, it’s abstract and unexplained, so the viewer has to let themselves be drawn into the piece.

Once flower_gan has that attention, the work shifts. As the context is slowly revealed, the datasets, the energy costs, the contradictions, the beauty starts to feel unsettling. That tension between attraction and discomfort is intentional. It mirrors how we often experience new technologies: initially drawn in, only to be unsettled when we understand what is hidden.

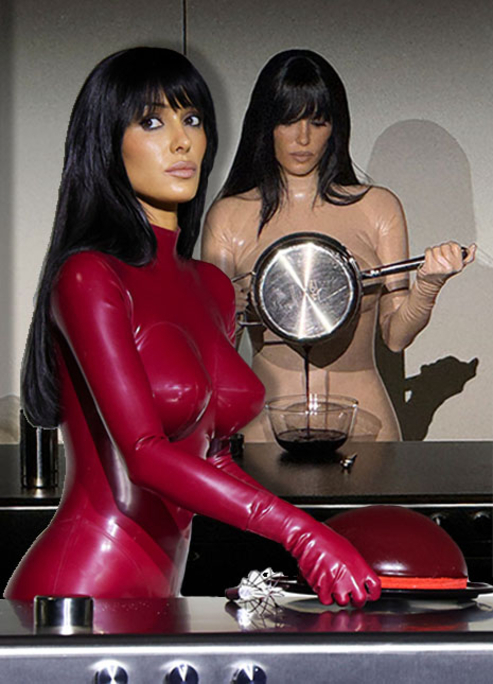

As flower_gan continues to circulate in festivals, exhibitions, and critical discourse, Mati Granica’s work reminds us that the most powerful critiques of technology often emerge from within its circuits. His art is not simply about artificial intelligence—it is made with and against it, exposing the fragile beauty and embedded violence of systems we too often take for granted.

With a practice rooted in visual seduction and conceptual resistance, Granica opens up urgent conversations around sustainability, scale, and the futures we’re engineering—whether we intend to or not. As the AI boom continues to reshape creative industries and ecological realities alike, voices like his are more necessary than ever.

Art & Photography courtesy of Mati Granica.