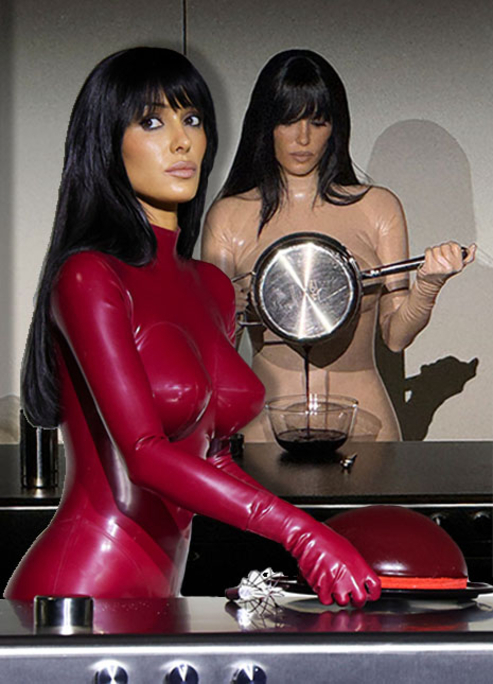

Perfect Hell: Berlin’s Beautiful Chaos Through Dennis Scholz’s Lens

Skateboarding roots, analog vibes, and the city’s wild contrasts collide in this bold photo exhibition you don’t want to miss.

Dennis Scholz, a 31-year-old photographer based in Berlin, is about to unveil his latest exhibition, Perfect Hell. Growing up near the city, Dennis got his start in photography through skateboarding, capturing his friends' tricks on camera. What began as a way to freeze those fleeting moments quickly evolved into a deeper exploration of how to capture intensity and emotion. Now, working in fashion and advertising photography, Dennis blends that raw, authentic energy with a more polished approach. His unique style, which mixes the gritty with the refined, is exactly what Perfect Hell is all about.

Dennis, your exhibition title, Perfect Hell, is quite striking. What does it mean to you, especially in the context of your photos and Berlin?

Exactly, that’s the point—it should be striking. I chose the title very intentionally because the two words are so opposite. The whole exhibition is built around pairs of images, each showing something very contrasting or contradictory. The idea is to shine a light on Berlin through its contrasts, as I perceive them—these little or big contrasts, these sharp cuts. It’s about showing situations where the same object or place is used in completely different ways by different people. The goal is to highlight these contradictions that, when placed side by side, actually end up working together in a surprisingly harmonious way.

You have a background in skateboarding, which influences your photography. How has it shaped your style?

I’d say skateboarding taught me a lot of things. For one, it helped me think about incorporating architecture into my shots and stepping back to show the subject in its environment. These days, I’m shooting all kinds of things beyond skating, but that’s still something I bring to my work—showing the subject in context and making it fit into the scene better. Another thing skateboarding taught me is to be fearless, in a way. This fits well with Perfect Hell because a lot of the shots are pretty bold, raw, and in-your-face. The exhibition itself isn’t really about skating, stylistically or thematically, but skateboarding definitely shaped how I move behind the camera and how I communicate with my subjects.

Berlin plays a central role in your work. What aspects of the city are most significant to you, and how do they shape your art?

I’d say that, this time, the people of Berlin take center stage. The focus is primarily on how different people perceive and interpret various places, objects, or activities in their own unique ways. And, as you mentioned, Berlin is the only place where this whole project was shot. The city itself is just such a melting pot of different, crazy, wild people who come together and somehow exist in surprising harmony, functioning really well together despite their differences.

And over what period of time were the photos taken?

It was exactly two months—roughly from the end of August to the end of October.

Your work often captures real moments and interpersonal dynamics. How do you achieve this?

For this project, I’d say capturing real moments was the central focus. It was all about showing the city and the people exactly as they are. Actually, I’d say I pushed it a bit further for this exhibition because it took me out of my comfort zone. I’m not the type of person who goes out every day to shoot street photos or hangs around Alexanderplatz looking for wild people. So, this was a bit more than I’m used to. But I think, in any context—whether it’s a big commercial shoot or a personal project—you can really feel the relationship between the photographer and the subject. You can tell if there’s a strong distance or if the two people have some kind of connection, like they know each other or have spent time together before the shot is taken. I think that comes through strongly in the images and translates really easily to the viewer. That’s why the interpersonal side of things is super important to me.

Why did you choose to focus this entire exhibition on Berlin?

There are several reasons. Mainly because it’s my home, the place where I live and spend most of my time.

Are you from here originally?

I’m from near Berlin, in Brandenburg, around Cottbus. But I’ve been living in Berlin for about 12 or 13 years now, so I’d definitely consider it home. Also, the exhibition is part of a collaboration between Kodak, the film manufacturer, and HUF streetwear, which supports creatives worldwide by giving them exhibition space to do their own thing in their respective cities. So, Berlin was kind of a given, and the concept itself came from me.

You shot the project using analog photography. Why do you like this medium?

One reason is that Kodak is involved—big thanks and shout-out to them. But also, I think digital photography would have had a completely different feel and might not have worked as well. With digital, you could just keep your finger on the shutter and shoot endlessly in certain situations, which doesn’t work with analog. With analog, you have 24 or 36 exposures, and the camera is much slower. This means you really have to immerse yourself in the situation and get as close as possible. That’s what makes analog special for me—it adds a much more personal touch to the work.

Contrasts are a recurring theme in your work. How do they manifest in this exhibition?

There are a lot of contrasts in this exhibition, as I mentioned earlier, especially between how people interpret places and objects. It’s about showing how the same place or object can be used in completely different ways by different people. For example, a bench might be seen by a skater as a playground to do tricks, while it’s traditionally meant for resting. This clash of uses is a simple example, but there are deeper societal contrasts as well. Like the woman in a fur coat because she can afford it, versus someone in a Mickey Mouse costume at Alexanderplatz, trying to make a few euros for dinner. Both involve dressing up, but they come from completely different places and serve entirely different purposes. That’s the angle from which I wanted to explore these contrasts.

You’re also launching a zine alongside the exhibition. How does it differ from your other projects?

Exactly. The zine is an extended version of the exhibition. It has about 44 pages, and in addition to the images shown in the exhibition, it includes many more photos and image pairs that didn’t make it into the show but are still strong enough to be brought to life on paper. The difference is that the project is much more personal. It’s essentially society seen through my lens, focusing on the idea that we’re surrounded by strong contradictions and contrasts.

You balance commercial work with personal art. How do these worlds influence each other?

That’s a really good question. I think one is very dependent on the other. Commercial projects give you the freedom to pay your rent, but they also allow you to do the things you’re really passionate about, like personal projects or strong artistic work. The commercial work is more about fulfilling a brief, and it’s more like assembly line work at times. However, it’s always built on the personal projects you’ve done before, which help you find your style and get your work out there. So, while they’re two completely different worlds, they really do feed into each other. I’m often booked for commercial work that reflects what I’ve done in my projects. So, as different as these two areas are, they really complement each other. That said, I could definitely be better at carving out more time for my personal work.

What do you hope people take away from Perfect Hell?

I’d love for people to understand the concept behind it and see the connections I’m making. Many will probably just take the images in at first, without really thinking about the theme. So, it’ll be interesting to see if they can grasp the idea and notice the connections between the photos. What I hope most is that people walk away understanding the concept and thinking, "Okay, now I get it." Ultimately, it’s not super political or societal critique, but it offers a new perspective on the city and the society we live in. If it encourages people to look at the world with a bit more awareness, I’ll be happy.

So, if you’re in Berlin and want to check out Dennis Scholz’s work in person, the show opens at Schivelbeiner Str. 9 on Saturday, December 14, at 7 PM.